Anthony Shadid

Anthony Shadid, a foreign correspondent for the New York Times, died last week, apparently of an asthma attack, while he was reporting in Syria. Until December 2009, he served as the Baghdad bureau chief of the Washington Post.

Shadid won the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 2004 for his coverage of the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the occupation that followed. He won the Pulitzer Prize again in 2010 for his coverage of Iraq as the United States began its withdrawal. In 2007, he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of Lebanon. He has also received the American Society of Newspaper Editors’ award for deadline writing (2004), the Overseas Press Club’s Hal Boyle Award for best newspaper or wire service reporting from abroad (2004) and the George Polk Award for foreign reporting (2003).

Shadid won the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 2004 for his coverage of the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the occupation that followed. He won the Pulitzer Prize again in 2010 for his coverage of Iraq as the United States began its withdrawal. In 2007, he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of Lebanon. He has also received the American Society of Newspaper Editors’ award for deadline writing (2004), the Overseas Press Club’s Hal Boyle Award for best newspaper or wire service reporting from abroad (2004) and the George Polk Award for foreign reporting (2003).

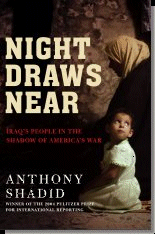

Shadid is the author of three books, Legacy of the Prophet: Despots, Democrats and the New Politics of Islam, Night Draws Near: Iraq’s People in the Shadow of America’s War, and House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family and a Lost Middle East, which will be published this month by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

From Shadid's Q&A with Houghton Mifflin about House of Stone, posted at the Wall Street Journal's Speakeasy blog:

How did the idea for this book come about?Also see: Anthony Shadid's favorite book about theocracy.

I guess there was always an idea in the back of my mind to do something about the family’s house in our ancestral town of Marjayoun. Even after wars and abandonment, it was still a grand place, and the idea of somehow reclaiming something that was lost captivated me. But it wasn’t until the war in 2006 in Lebanon that the idea became more than a fleeting thought. The conflict, which pitted Hezbollah against Israel, is just one of the many that litter the modern Middle East, but in the death and destruction, I found it one of the most wrenching to cover as a reporter, even worse than Iraq. After it ended with a cease-fire, I made my wayto my grandmother’s house in the town, not too far from the frontlines. In the distance, I could hear the rotors of a helicopter beating against the air and the insect-like drone of surveillance planes. I walked over to an ancient tree there, and as I sat next to it, an olive dropped beside me. I don’t know why I found the moment so memorable, even all these years later. I guess it was after so much bloodshed, so much loss, I was finally witness to something so tranquil. It fell naturally, its movement dictated by time, not will, malice, or the menace of war. Right then, I had a feeling that this was where I wanted to be. The next year, I was, rebuilding the house and trying to figure out whether it could become a home.

Did your grandmother’s house eventually become a home?

I suppose it became something more than a home in the end. I’ve always felt that home is simply where we want to be. But I think in my time in Marjayoun, I realized that we can understand home in a much broader sense. We can imagine it as memory, community, history, and even identity. At some point, home is the way we make sense of ourselves.

On a personal level, what is it like to build a house?

Endlessly frustrating. I knew building a house in a country that is often dysfunctional would be a tough task, but I had no idea that I might stumble on a painter who was color blind, a foreman so stingy he argued over a few cents, and a carpenter who...[read on]

Writers Read: Anthony Shadid (August 2007).

--Marshal Zeringue